Breaking Convention

Where did hostility to the ECHR come from? Could it be valid?

These days, a regular occurrence on the British Right is to curse the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and to demand we exit from it. Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch recently launched a review on this very subject, to be chaired by Lord Wolfson of Tredegar who is currently the shadow attorney general.

Badenoch and the Right more generally have two two main areas of concern regarding the convention and the associated European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in Strasbourg (sometimes referred to as ‘The Strasbourg Court’). These two concerns are:

ECtHR/ECHR judgments sometimes overturn, constrain, or neuter parliament’s will and, by extension, the democratically expressed will of the British people. One might call this ‘the principled concern’.

The ECtHR/ECHR appear to stand in the way of certain specific policies, in particular on immigration and even more specifically on the deportation of unwanted foreign nationals. A ‘policy-specific concern’.

Suffice it to say, in launching a review of the ECHR and its impact on Britain, Kemi Badenoch is running behind more populist figures like Nigel Farage and Robert Jenrick who are demanding immediate exit from the ECHR. All the pressure within the Right is therefore moving in a more ‘exity’ direction.

The purpose of this article is to look at where this hostility came from. Does the Right have a point? And why is this turning into another front in the culture war?

A quick romp through history

There are some who think attacks on the ECHR form a second populist wave after the first wave - Brexit - fell short of their expectations. But while ECHR-scepticism has seemingly ramped up post-Brexit, it has always formed a second 'trunk' arising from the same principled concern about protecting/restoring untrammelled parliamentary sovereignty.

These two trunks - scepticism of the EEC/EU and scepticism of the ECHR - were born at the same time after World War II alongside the new European dimension in our continent's politics.

ECHR-specific scepticism started while the ECHR was still being forged within the Council of Europe. Members of Clement Attlee's Labour Government (1945-51), especially the then Lord Chancellor, William Jowitt, saw the ECHR as potentially compromising the sovereignty of parliament.

Indeed, the Attlee government argued within the Council of Europe for only a limited set of rights in the proposed convention as Britain saw a 'thin' ECHR as purely a device to prevent dictatorship. Other governments wanted a ‘thicker’, more active ECHR with a somewhat broader role.

The Attlee government had further wanted to limit individual citizens’ ability to complain about rights violations under the ECHR. Other countries thought otherwise. Consequently, it was eventually agreed that states could decide themselves whether to give this right to their citizens and indeed whether or not to accept the new Court’s jurisdiction.

And so the ECHR went ahead in a thinner form than we know today, and Britain was among the first to sign in November 1950. It finally came into force in 1953.

But yes, the sensitivities about national parliamentary sovereignty were very much in play during the ECHR's formation, and just like EEC/EU membership, Britain was the leader of the sceptics. Others who had argued for a 'thinner' ECHR were eurosceptical Norway and Denmark.

In its early years, this tension between 'thin' and 'thick' interpretations of the ECHR played out in the ECtHR itself.

In 1966, the UK finally recognised the jurisdiction of the Strasbourg Court and also accepted the right of UK citizens to petition it directly. This set the stage for future tensions especially as the ECtHR began issuing rulings that required changes to UK laws.

However, concerns about the ECHR were rather muted during the late-1960s and 1970s, largely because so few cases were brought before the Strasbourg Court and so few violations found. The centre-stage topic of EEC membership may have been a distraction too.

A landmark ECHR case in 1981 pushed the Thatcher Government to legalise homosexuality in Northern Ireland despite opposition from some backbench factions led by fiercely anti-EU MP Enoch Powell. This case would fire the starting gun on renewed ECHR-scepticism. Here is Powell in Hansard in 1982....

During the Thatcher period, other Northern Irish & IRA-related cases further stoked ECHR scepticism, but it was really post-1988 - a crucial year in the wider history of Brexitism - that a new generation of Tories took such scepticism forward. And one man was key: Michael Howard MP.

A known eurosceptic, Howard was also the Tory hard man of Law & Order. He was first assigned to the Home Office in 1989 and was Home Secretary from 1993-1997. It wasn't long before he became critical of the ECHR and its "judicial activism".

Howard sensed what Sun readers wanted:

“Prison works. It ensures that we are protected from murderers, muggers, and rapists—and it makes many who would otherwise be tempted to commit crime think twice.”

Clashes with the ECHR were inevitable. One might even call him Britain's first Populist.

Legal clashes did indeed happen - on the IRA, on prisoners’ rights, and on deportation - but it was one terrible case in 1993 at the start of Howard's time as Home Secretary, that really helped define him and his approach to the law. That was the case of James Bulger.

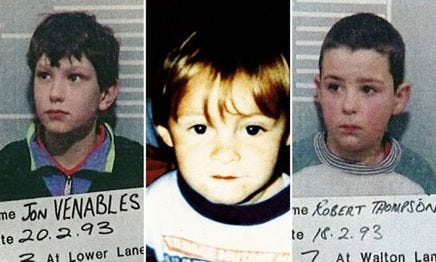

Anyone sentient in Britain in the 1990s knows about the James Bulger case. It remains one of the most chilling of modern times - a case that is beyond comprehension, and still reverberates to this day. Two boys aged 10 – Robert Thompson and Jon Venables – abducted 3 year-old James Bulger in a shopping mall and then murdered him.

The trial judge had no real choice in sentencing due to the boys' age. They would be detained at Her Majesty's pleasure until the Home Secretary of the day was satisfied they could be released. The judge recommended they serve at least eight years.

Result: widespread fury.

The Sun newspaper hastily organised a petition demanding full life terms for both boys. They even had a coupon printed in the paper that readers could cut out and send to Michael Howard demanding "prison for LIFE". Thousands contacted MPs and TV & Radio stations in uproar.

Rarely before was such a clash set up between the law and popular demand. Michael Howard's response to all of this was to unilaterally increase the tariff to 15 years, overruling even the Lord Chief Justice's advice. It was a populist move in response to the public's clamour for vengeance.

Howard was eventually slapped down by The House of Lords but the anger rumbled on. The next act occurred when Howard had gone, and Tony Blair's Government had taken over. In 1999, the ECtHR found that the two boys had been denied a fair trial.

In June 2001, notably eight years after conviction as per the trial judge, the two boys were released under strict conditions and given new identities. The press have continued to be fascinated by them. Several individuals have been prosecuted for posting alleged photos of the two.

However the Tories were out of power from 1997-2010 and the ECHR was incorporated into the Human Rights Act in 1998 by the Blair Government, so one might have thought that the ECHR would then somehow fade into the background.

Not at all.

Labour Home Secretary Jack Straw soon went wobbly on the issue:

"I now fully understand that [Daily Mail readers] have concerns about the Human Rights Act. There is a sense that it’s a villains’ charter or that it stops terrorists being deported… I am greatly frustrated by this. Not by the concerns, but by some very few judgments that have thrown up these problems.”

Another Labour Home Secretary, David Blunkett also sounded rather populist, with the ECHR and the judiciary more broadly were on his radar:

“If public policy can be always overridden by individual challenge through the courts, then democracy itself is under threat”.

Michael Howard (and Nigel Farage) would have approved.

Next to be promoted into the job of Home Secretary was Dr John Reid. He wanted a full review of Human Rights legislation including the ECHR, but ran into opposition from his cabinet colleagues.

Indeed, it might now be said that the Blair-Brown Governments provided an ECHR-sceptic bridge between the 1990s Michael Howard period and the Cameron Governments of the 2010s.

The 2010 Tory manifesto pushed the idea of a new British Bill of Rights in place of the Human Rights Act (HRA) of 1998. This was not carried through into the coalition government with the Libdems, but Justice Secretary Kenneth Clarke and Attorney General Dominic Grieve did manage to negotiate a reform of the ECHR via ‘The Brighton Declaration’ in 2012.

Some would say The Brighton Declaration proved that reform of the ECHR was entirely possible when approached in a constructive way. Clarke and Grieve were both pro-Europeans.

The 2015 Conservative manifesto [PDF] toughened the language on the ECHR by seeking a reversion to the ‘thinner’ ECHR of old, but Brexit then took over and any thoughts about the ECHR faded into the background.

But notably during the EU referendum campaign of 2016, before she became Conservative leader and prime minister, the then Home Secretary Theresa May said the following:

“The case for remaining a signatory of the European Convention on Human Rights – which means Britain is subject to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights – is not clear. Because, despite what people sometimes think, it wasn’t the European Union that delayed for years the extradition of Abu Hamza, almost stopped the deportation of Abu Qatada, and tried to tell Parliament that – however we voted – we could not deprive prisoners of the vote. It was the European Convention on Human Rights.

The ECHR can bind the hands of Parliament, adds nothing to our prosperity, makes us less secure by preventing the deportation of dangerous foreign nationals – and does nothing to change the attitudes of governments like Russia’s when it comes to human rights. So regardless of the EU referendum, my view is this. If we want to reform human rights laws in this country, it isn’t the EU we should leave but the ECHR and the jurisdiction of its Court.”

As part of Brexit, the UK agreed new arrangements with the EU - the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) - that explicitly committed both the UK and EU to the ECHR for human rights protection. The UK leaving the ECHR would therefore put the UK in breach of the TCA, prompting retaliatory action from the EU. Also, the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) of 1998 required the ECHR to be part of the law in Northern Ireland. ECHR-exit could therefore unravel the GFA with potentially serious consequences for peace in Northern Ireland.

In 2022, after Brexit, the government ran up against the ECHR over the controversial Rwanda deportation scheme. This policy spanned the consecutive leaderships of Boris Johnson, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak. Article 3 of the ECHR, which prohibits torture, inhumane or degrading treatment came into play, along with ‘Rule 39 Interim Measures’ blocking UK government action. This played a significant role in preventing the first deportation flight to Rwanda and this newsworthy fact proved to the Right that “European Institutions could still meddle in our laws, despite Brexit” - a crude statement that nonetheless played heavily across the populist ecosystem.

The Conservatives comprehensively lost the General Election of 2024 and elected Kemi Badenoch as their leader in opposition, which brings us full circle to the Badenoch-sponsored review of Britain and the ECHR.

It looks like the Right is starting to fully position itself for an ECHR exit.

Do the ECHR-sceptics have a point?

There is unquestionably a history of governments of different colours being prevented by the ECHR from doing certain things with undesirable foreign nationals. Indeed, Theresa May touched on the two most newsworthy cases in this context - those of Abu Hamza and Abu Qatada. These cases related to Islamist radicalism/terrorism and caused the tabloid press to get very animated whenever the courts - especially the ECtHR - stood in the way of expelling these individuals. The government happily stoked and went along with the general sense of outrage at their ‘soft’ treatment.

But such cases tend to provide a poor basis for argument, wrapped as they are in emotive outrage. Furthermore, such cases are policy-specific. Strip that away, and the Right is still fundamentally arguing about its principled objection: that the ECHR/ECtHR can undermine parliamentary sovereignty and the democratic wishes of the British people.

I’m grateful here to former Supreme Court judge Lord Sumption, who is perhaps the most respected legal advocate for ECHR-scepticism.

A key layer of the ECHR-sceptic case as set out by Lord Sumption is about which human rights should be considered fundamental or ‘inalienable’ and therefore taken outside the ebb and flow of normal democratic politics. Rights such as the right not to be killed or the right to have recourse to independent courts if wronged. Also in this category are rights without which a country cannot function as a democracy. For example, rights to free speech and free association, and a right to free and fair elections.

But - so the Sumption argument goes - if there is scope for debate between reasonable people about whether a particular right is fundamental, then that right becomes contentious and should instead be the subject of ongoing democratic debate. It should therefore not be codified as ‘inalienable’.

Ultimately, this is an argument for the ‘thinner’ ECHR as debated back in the 1940s, and apparently called for again in the 2015 Conservative manifesto.

There is however another layer to this. Not only does Lord Sumption and the Right object to the ‘extended scope’ of the ECHR into areas they believe should be the exclusive competence of democratic politics, but their deeper objection is that the ECHR is a ‘living, dynamic instrument’ - one whose interpretation is developed by the ECtHR such that it encroaches into more and more areas over time. And it is the ‘living instrument’ doctrine of the ECHR and ECtHR that has led the Strasbourg Court to stray into areas more properly reserved for democratic politics. It is this that is really pushing ECHR-sceptics towards ECHR-exit.

Article 8 of the ECHR is cited by Lord Sumption as a good example of the living instrument doctrine. The Article guarantees the right to respect for private and family life, home, and correspondence. It was originally written to protect against the surveillance state in a dictatorship - remember the purpose of the ‘thin’ ECHR being one of guarding against dictatorship. But the ECtHR has subsequently expanded the meaning of Article 8 into one about ‘personal autonomy’. It can now cover anything that intrudes on someone’s personal autonomy, and thus gives an individual much greater rights over a swathe of policy areas that were never envisaged when the ECHR was first drafted. Moreover, that this gradual change has made such rights contentious and therefore no longer inalienable.

The whole concept of the ECHR as a living instrument is another way of expressing something the Right often objects to: that of ‘Judicial Activism’ and ‘Rule by Judges’.

There are, quite obviously, arguments on the other side - arguments that favour maintaining our involvement with ECHR/ECtHR. It is not the purpose of this Substack to set out exhaustively what all the arguments are (on both sides), but briefly:

Leaving the ECHR would mean difficulties for both the TCA with the EU and the GFA with respect to Northern Ireland.

Existing ECHR arrangements act as a commitment device, not only for ourselves but for other countries across Europe.

Being outside the ECHR would put us in poor company e.g. Belarus.

The ECHR confers advantages on us, not least (for the Right) a constitutional right to free speech. Cases taken to the Strasbourg Court have supported such rights.

Since the Brighton Declaration, there have been relatively few ECHR constraints on British government action.

A British government can reject the judgment of the ECtHR. And they have done so.

Sumption has at times suggested that an ECHR withdrawal would involve almost replicating the ECHR text in British law - the key point being that this text is then solely subject to the British parliament, who can change it more easily than trying to bring about change at European level. If the text then becomes a living instrument, parliament can steer it or even reset it through legislation.

Separately, Sumption has suggested that Northern Ireland should remain subject to the ECHR/ECtHR if the rest of UK left.

Over all, though, the Sumption argument is a logical and reasonably-held one. On the matter of human rights, there is a legitimate debate about where the line should be drawn between law and politics, and moreover, how that line is to be governed and by whom.

Conclusions

So if Sumption’s argument is a reasonably-held one, even if one may disagree with it, why is this becoming another front in the culture war: a ‘Brexit 2.0’, that is causing a lot of liberals and conservatives to get increasingly animated?

The problem arises from populism. Put another way, Lord Sumption is one person who is arguing his case from a mostly legal standpoint. But we cannot rely on his voice carrying over, untainted, into the political realm. Dare I say it, but he sounds suspiciously like ECHR-scepticism’s ‘Liberal Leaver’ - a ‘high principle’ but ultimately naive, middle-of-the-road exiter, who will get flattened by the bulldozer of populism at the first opportunity, which then leads to a blundering and damaging exit.

‘Brexit 2.0’ may be a good characterisation after all.

The clues are already there: Lord Sumption parts company with the dafter elements of the Right over a number of policy areas, from the Rwanda scheme to ‘free speech martyr’ Lucy Connolly. He is therefore not representative, even though a lot of his ECHR arguments chime with others on the Right.

After the whole Brexit experience, we need to be alert to such naivety. But I would also suggest we are now in a more Trumpian-Populist world where we need to maintain checks and balances on ‘untrammelled sovereignty’ and executive power, not exit from them. The populist position of “the will of the people (against the elites) everywhere all of the time” is a constant and genuine threat to such checks and balances, with the ECHR being an obvious first target. It won’t be the last.

In these circumstances, the need to defend the existing human rights regime becomes clearer and indeed more pressing.

Can these rights be defended?

I think so, but be under no illusions that if/when ECHR attacks from populists really start rolling, who would be “on the side of the Bulger killers”? That's the emotive stuff that'll be thrown around. And it'll need some good answers.

Further reading:

The Impact of the European Convention on Human Rights on UK National Security, by Lord David Anderson of Ipswich KBE KC, May 2025 (Covers a fair amount of ground - from William Jowitt to Lord Sumption)

Lord Jonathan Sumption vs Dominic Grieve on leaving the ECHR (Youtube)

David Allen Green in Prospect Magazine, June 2025: ‘The European Convention on Human Rights needs practical reform, not quitting’. Covers the question of Article 8.

Many thanks for the analysis of the ECHR and the court. Much appreciated

What I find disengenuous about Sumption's argument is all legislation is a "living thing" subject to analysis and interpretation whether it defines human rights or the highway code.

Laws can be challenged, repealed, rewritten and overturned so seeking reform of the ECHR should be viewed as more of the same, albeit somewhat more complicated.

The easy way out for him and those who'd gladly destroy anything getting in the way of their simplistic but harmful snake oil cures, would be to leave altogether.

However they and he should keep in mind the number of occasions over many recent years, how the will of the Commons was stymied with good reason, not only by the ECtHR, but also the unelected House of Lords of which he's a member.

Really pleased to read your thoughts in Substack format 🙂. BlueSky and the other thingie that went fascist wore me out, but blogging can be more measured and less addictive to follow. I shall miss the curation of Torygraph headlines, but they were veering into self-parody, almost as if they were written with a view to being sh1tposted.